What do artists like William Morris, British designer, manufacturer, and writer, and Chris Lebeau, Dutch graphic and textile designer, have in common?

At first glance, they might seem different due to their nationalities, and Lebeau may be less recognized outside of art circles, however, these two artists shared significant similarities, particularly in their artistic period and movement. Most notably, they both had a keen interest in Art Nouveau textile motifs.

We often associate the history of cotton fabrics in the Netherlands to the Dutch East India Company (VOC) which imported textiles that suited the Dutch taste in clothing and decorator fabrics from the Coromandel coast of India. Yet, in the islands of the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia), another fabric played a significant role in the lives of both Dutch colonists and Indonesian people: batik.

While batik originated from the island of Java, the precise time of its inception remains a topic of discussion. Batik is not only a method of fabric production but also a material of immense cultural significance within Indonesia. The technique was initially documented in Europe through Stamford Raffles’ “History of Java,” published in London in 1817. Later, in 1873, the Dutch merchant Van Rijckevorsel introduced batik pieces to the ethnographic museum in Rotterdam. Since the creation of the VOC in 1602 and the establishment of colonial outposts in the Dutch East Indies, numerous Dutch officials and civil servants facilitated considerable cultural and material exchanges between the Netherlands and the Dutch East Indies — evidenced by many Dutch still-life paintings from the 17th century onward, which often depicted exotic seashells and items originating from the colonies.

This unique Dutch interest for oriental motifs grew and significantly influenced artists, particularly during the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900.

Dutch graphic and textile designer Chris Lebeau was largely responsible for the popularity of batik textiles in the Netherlands. He established his own batik studio in Haarlem in 1902, where he created machine-made textile designs. These affordable designs reached a wide audience and were sold through ‘t Binnenhuis, a central hub of the Dutch Art Nouveau style, known as Nieuwe Kunst (“New Art”). This store dedicated to home furnishing, notably designed by the Dutch architect Hendrik Petrus Berlage, was founded in 1900 to counterbalance the art promoted by the Arts and Crafts movement. Many influential artists worked in this ‘art craft saleroom,’ playing a significant role in the evolution of Dutch Art Nouveau.

William Morris’ Arts and Crafts illustrations.

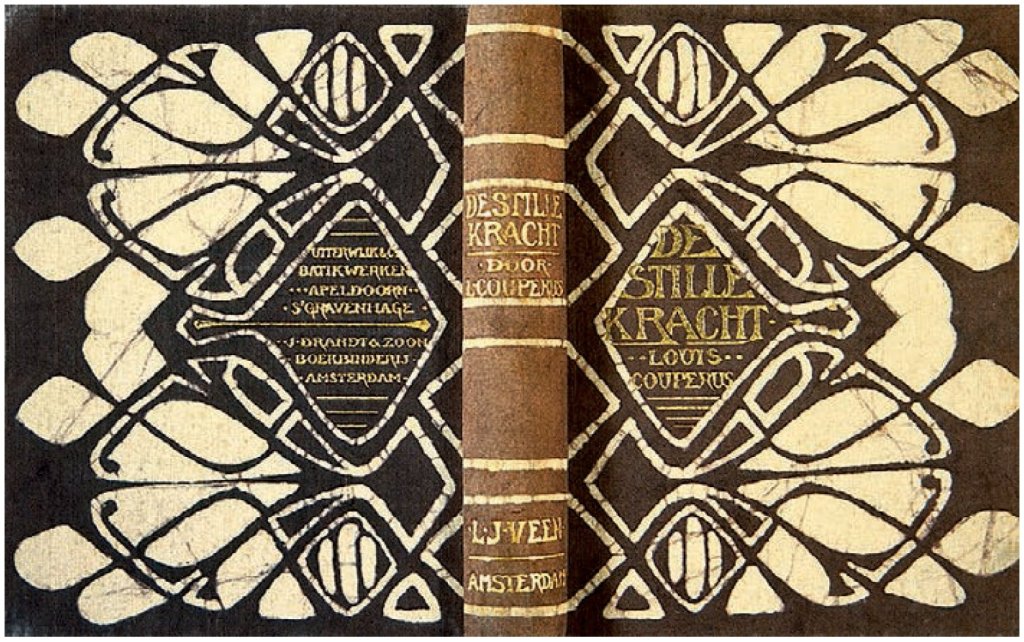

Lebeau designed batik cotton and velvet covers in several color variations for Louis Couperus’ popular novel set in the Dutch East Indies, De Stille Kracht.

Around the same time as Lebeau started working with batik, the Javanese technique began to be used and reappropriated actively by Dutch artists to decorate wall coverings, tablecloths and much more. Artists like Jan Toorop, Theo Neuhyus, Johan Thorn Prikker or Gerrit Willem Dijsselhof, were inspired by the arts and cultures of Indonesia and actively contributed to this batikmania.

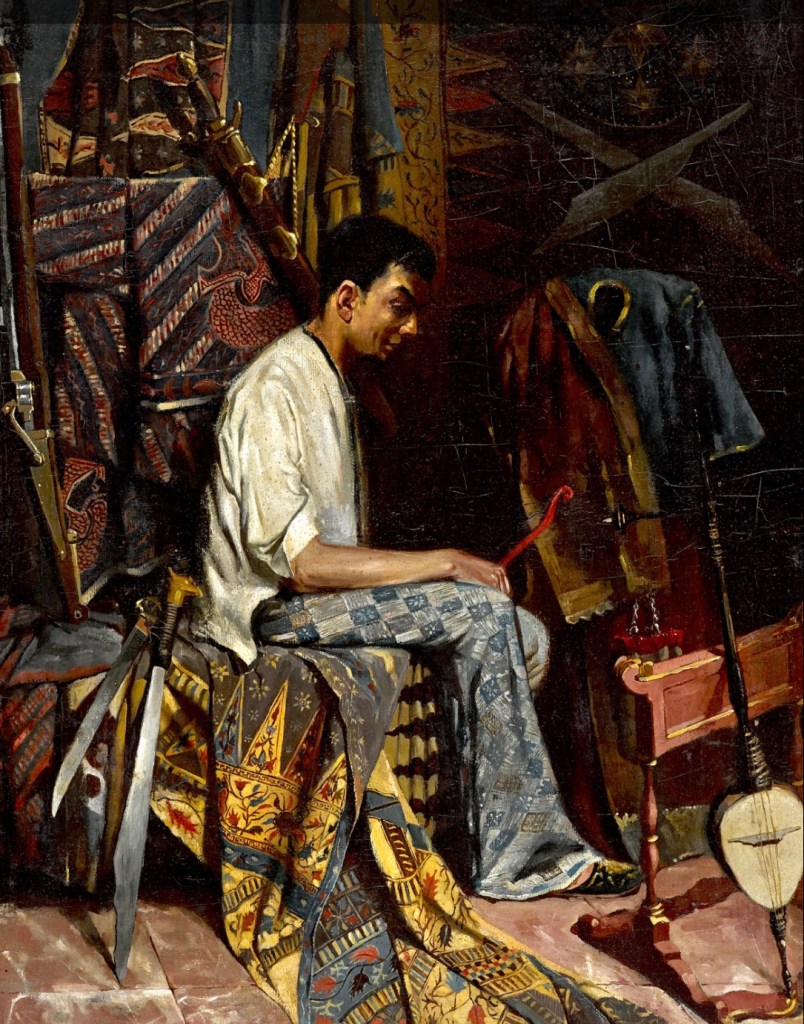

In a self-portrait from 1880, Jan Toorop depicts himself amidst elements of Javanese culture. The most striking aspect of this painting—apart from its unusual colorful palette rather atypical for Toorop—is the prominent display of various batik fabrics draping and stretching across the canvas. Here, the batik likely represents a Sarong, a large tube or length of fabric often worn around the waist, adorned with traditional Tumpal motifs, characterized by a series of triangular shapes. Near the sitting area in the painting are two Parang, headhunter’s swords with broad, curved blades used in Indonesia and Malaysia—a term that also interestingly refers to one of the oldest batik motifs.

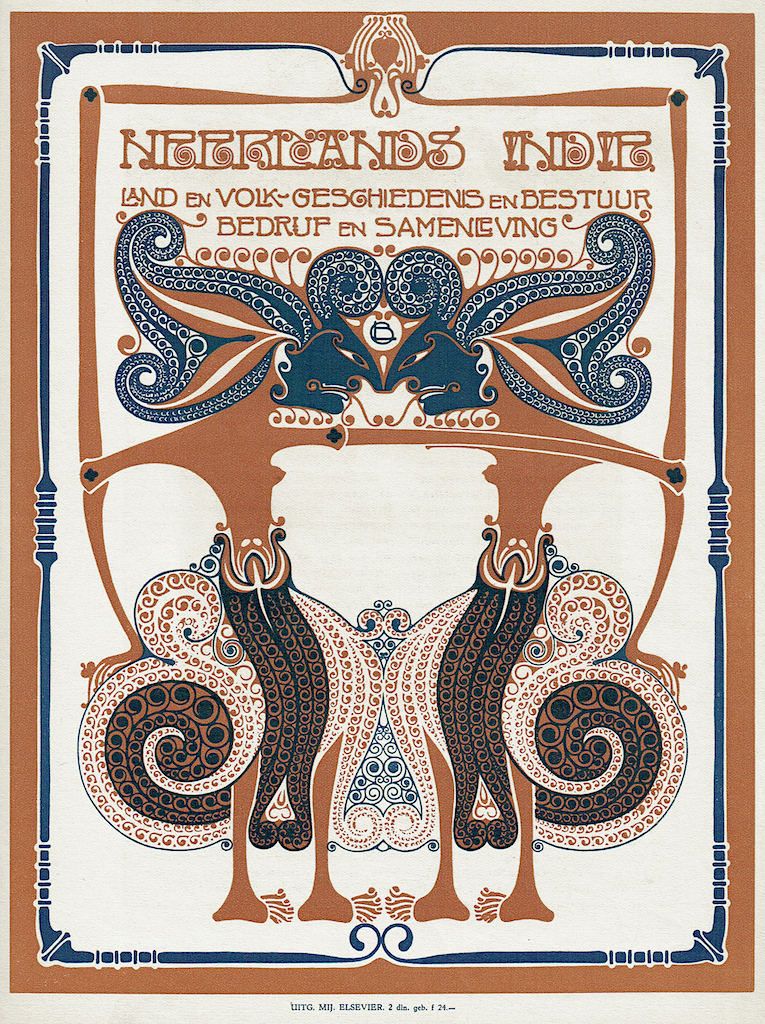

Toorop’s cover design for the book Neerlands Indië is a good example of how Dutch experiments with the Indonesian batik technique influenced Dutch graphic design. The cover features two wayang kulit— Indonesian puppet shadow show—figures in confrontation, mirroring traditional batik aesthetics not only in its hues of blue, white, and brown but also in the deliberate placement and separation of these colors. The spiral shapes in the image, each centered with a droplet-like figure, draw a distinct parallel to the shapes made when using a tjanting tool to apply fluid wax on fabric.

Quite around the same time across the Channel, a new artistic approach and vision had emerged. Under the leadership of William Morris, and along with the esteemed English poet, philosopher, and writer John Ruskin—whom he deeply admired—the Arts and Crafts movement was in full swing. This movement was a direct reaction against the ‘betrayal’ brought about by industrialization and the explosion of mass-produced goods during the Industrial Revolution. Indeed, Morris and Ruskin held a conviction that happiness could be found in handicraft. Their mission consisted of integrating art into the home by reevaluating the work of craftsmen, whom they felt were marginalized by the industrial era. In other words, they believed the production of objects should be part of a much broader vision of society, one that is mindful of social progress and the elevation of humanity.

Furthermore, Morris and Ruskin advocated for the necessity of living and working in a healthy and pleasant environment to produce quality work. As a result, communities of artisans began leaving the city to settle in the countryside, closer to nature.

In 1852, when Morris joined Oxford University, he developed a profound interest in medieval history and architecture, spurred by the city’s abundance of medieval buildings. As a student of architecture and then painting, he formed friendships with artists who were members of the “Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood,” such as Edward Burne-Jones and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, with whom he shared convictions and ideals. The artists of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood were a group of painters seeking to rediscover a certain authenticity in art that they felt was lost due to the effects of industrialization and commerce.

Drawing inspiration from this philosophy, Dutch painter Gerrit Willem Dijsselhof, himself involved in the Arts and Crafts movement designed several book covers and color lithograph calendars, focusing on nature and animals as well as the use of batik textile.

Gerrit Willem Dijsselhof, magazines, 1893-1906

Member of the Natura Artis Magistra, a zoo and botanical garden in Amsterdam, he was commissioned by dermatologist Willem van Hoorn in 1895 to design a complete interior for his Amsterdam home. This design, executed in the Art Nouveau style, aimed to create a Gesamtkunstwerk—a place that embraced all art forms, a vision he shared with William Morris. As a matter of fact, Morris aimed to create a comprehensive art form, giving equal importance to furniture, wallpaper, and fabrics. His Red House, designed in 1859, is a major example of this synthesis of the arts.

William Morris Red House interior and Gerrit Willem Dijsselhof Willem van Hoorn House interior.

The embroidery on the large batik panels on the walls was crafted by needle artist Willy Keuchenius, who Dijsselhof would later marry.

Furthermore, Theo Neuhuys, an early batik artist, contributed to the American arts and crafts magazine Ceramic Studio in 1907, explaining how to apply batik on parchment. He also created posters inspired by batik; his book covers, to some extent, are reminiscent of William Morris’s wallpaper designs.

Theo Neuhuys, Album, Almanak and Concert Programs, 1902, 1906, 1908.

The Netherlands and England share a long-standing common history in the textile industry. Even though England was the first country to introduce the use of new techniques and machines, like John Kay’s 1733 flying shuttle or James Watt’s steam engine, both nations exhibited notable parallels, including significant importation of Indian cotton, participation in the West African slave trade, and the flourishing of calico printing from 1600 to 1760.

Additionally, the Dutch East India and English East India companies played a significant role in the European market for Indian textiles during 1700-1800, albeit their strategies differed. While the English focused on acquiring the finest textiles at the most favorable prices in India, the Dutch were more liberal in their approach to Indian textiles, a stance that is sometimes said to have drowned out their own textile industries.