“You realize, Stevens, I don’t expect you to be locked up here in this house all the time I’m away. Why don’t you take the car and drive off somewhere for a few days? You look like you could make good use of a break.” Coming out of the blue as it did, I did not quite know how to reply to such a suggestion. I recall thanking him for his consideration, but quite probably I said nothing very definite for my employer went on: “I’m serious, Stevens. I really think you should take a break. I’ll foot the bill for the gas. You fellows, you’re always locked up in these big Houses helping out, how do you ever get to see around this beautiful country of yours?

Similar to Ishiguro’s Mr. Farraday, let’s stroll through the American countryside.

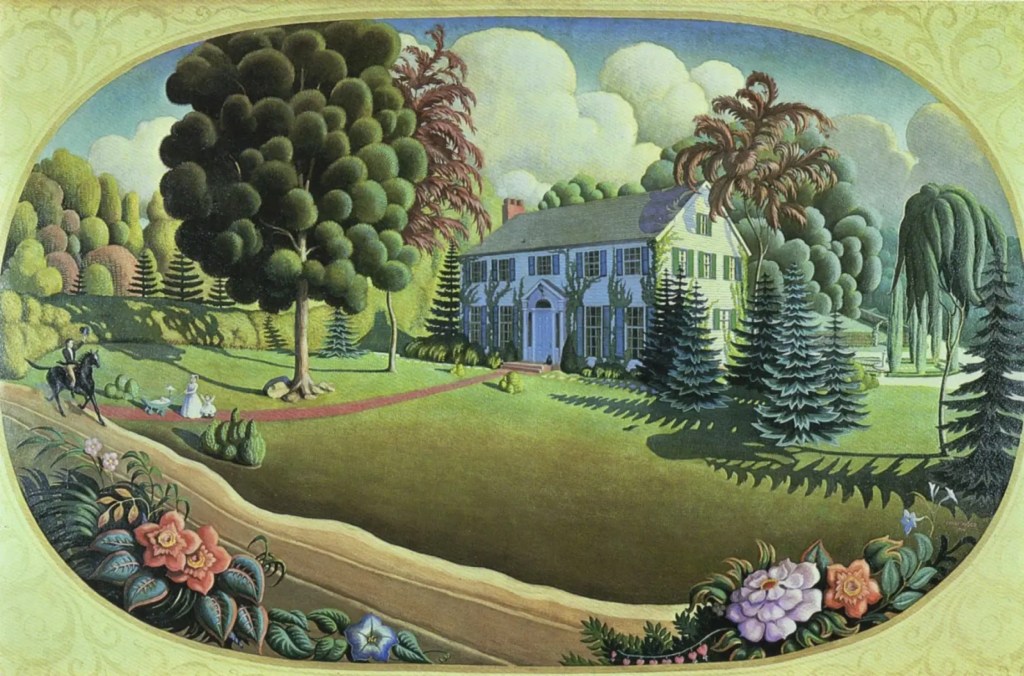

Grant Woods’ American rolling countryside paintings are imbued with daily village life and realism, but also a touch of abstraction, as something out of a childhood fantasy book. Wood emerged as a prominent figure in the 1930s American Regionalism movement, renowned for his stylized and nostalgic paintings depicting rural America and its foundational myths.

Spring in Town evokes a sense of nostalgia for the happy fantasy of daily rural American way of life before World War II, capturing the serene ambiance of small-town existence. Amidst the charm of the village houses, people are immersed in various activities, all in a sense of peace, homeliness, and individuality. The painting drew inspiration from the precise and detailed realism found in the works of 16th-century German and Flemish masters such as Jan Van Eyck.

The presence of industrial smokestacks alongside backyard gardens serves as a poignant reminder of bygone eras, evoking memories of the Great Depression and wartime victory gardens. The church overlooking the clean neighborhood of the single-family homes, reflects the religious beliefs of the community, while the factory in the distance hints at the ongoing industrialization of the region.

In this painting, Grant Wood casts in the middle of rural America two automobiles and a red truck teetering on the edge of a near-fatal accident. Even Flannery O’Connor‘s 1930s and 1940s rural country roads, referenced in her collection of short stories and poems titled The Complete Stories (1971), are not as steep, yet they are undoubtedly fraught with the potential for tragedy. In “A Good Man is Hard to Find” (1953), she narrates the unsettling journey of a Southern family embarking on a road trip to Florida. As they navigate the narrow roads, their journey takes a dark turn when they encounter The Misfit, an escaped convict, who dispassionately orders the murder of the Georgia family.

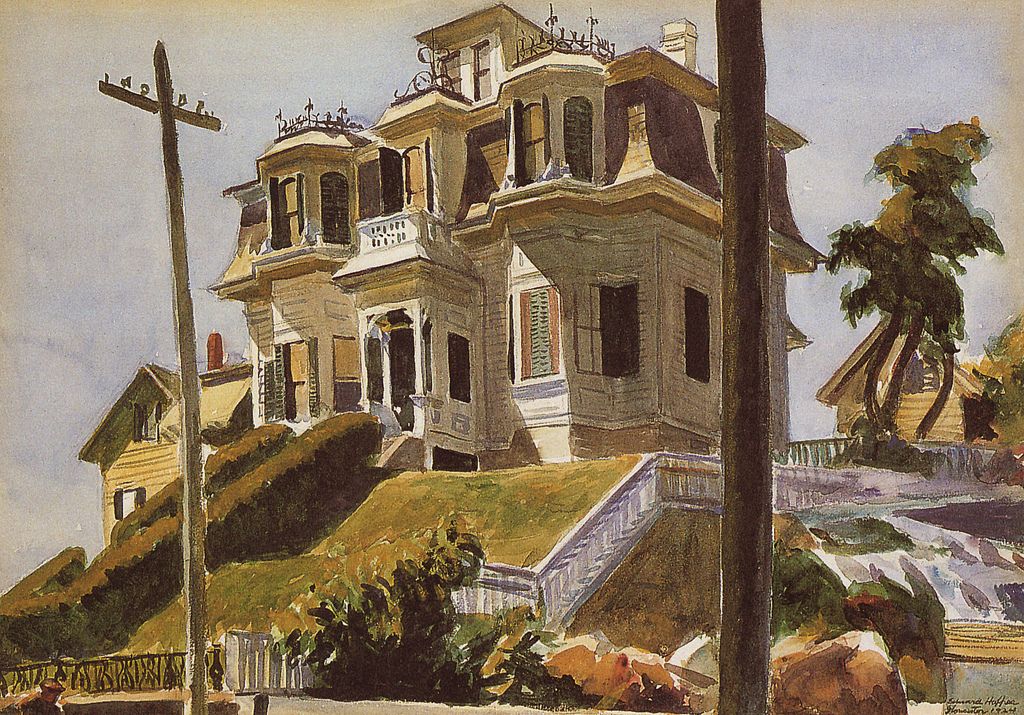

Edward Hopper, widely celebrated for his portrayals of urban solitude, ventures into a different territory with Haskell’s House. Here, he represents the residence of its owner at the time, Melvin Haskell, a master mariner and public servant. The house, perched atop a hill, seems to loom over the viewer with intent, akin to a stern parental figure.

On a late afternoon in the countryside, the sun pervades the windows and porch, and the yellowed grass dances in the post-noon breeze. Hopper’s House by the Railroad features a grand Victorian home situated near railroad tracks. Caught between isolation, tranquility, and the innovations of modern life, the painting plays with themes of isolation, innovation and mobility, capturing the rapid modernization of the rural ways of life of early-twentieth-century America. Almost like a Poe-like mansion, a vague feeling of anxiety, decay and dread seem to surround the house. It’s perhaps no coincidence that Victorian homes, with their array of towers, Gothic embellishments, ornate pillars, and broad verandas, have come to symbolize the quintessential haunted house. In fact, Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 film Psycho seems a likely source of such connotations, as does Edward Hopper’s House by the Railroad, which seems to have been the model for it.

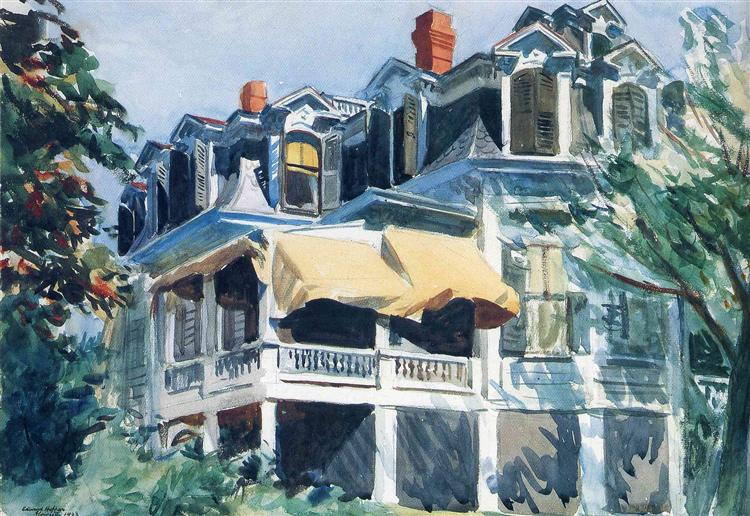

In 1923, Edward Hopper was still finding his artistic footing when he painted The Mansard Roof, a work that stands apart from the urban loneliness he’s famous for. After having met who would later become his future wife, fellow NY school of art student Josephine, who convinced him to go to Gloucester, MA, Hopper found inspiration in Victorian mansions. By the 1920s, with the Roaring Twenties and society going at full swing, old Victorian mansions had grown unfashionable and garish. In this simple scene, like a rooftop viewed from his back door, Hopper chose to side with a nostalgic vision of America and its Golden Age, refusing modern art motifs in favor of a realistic yet surreal watercolor portrayal.

In 1951, Thomas Hart Benton painted Flood Disaster, a testimony to the wreckage caused by massive flooding of the Kansas and Missouri rivers in July 1951 that killed 17 people and displaced more than half a million residents. The painting portrays a devastated landscape where two destroyed houses, a mangled car, and a mud-covered washing machine lie on the shore of the Kansas River. In 2011, Flood Disaster was auctioned at Sotheby’s and sold for nearly $1.9 million, exceeding its pre-sale estimate of $1.2 million.

The Missouri artist further emphasized the urgency of the flood victims’ suffering by sending lithographs of this artwork to each member of the Congress, urging them to support and expand a flood relief bill, but it was in vain, although $113 million in flood relief was signed by President Truman in October 1951.