Contemporary Nigerian artist Yusuf Grillo is a highly influential figure in Nigerian art history. Born in Lagos in 1934, he is celebrated for his inventive use of color, especially his signature shades of deep blue (a reference to adire and resist-dye textiles used in Nigeria), and for his expressive interpretations of Yoruba culture. His iconic stained glass and mosaic installations have been commissioned for numerous public spaces across Nigeria, including churches, universities, government buildings, and the Murtala Mohammed International Airport. This analysis centers on No Thanks, a work realized both as a painting and in stained glass, with particular attention given to the latter.

Stained glass was not initially Yusuf Grillo’s central focus. It was, in fact, Kavita Chellaram, director of Arthouse Contemporary, who first proposed the idea of translating one of Grillo’s paintings into the medium of stained glass. Grillo remembered that during his student days in Zaria, a lecturer, Clifford Frith, had once commented that his use of angular lines and flat planes made his paintings resemble stained glass.

After attending a workshop in Bradford, UK, Grillo began adapting stained glass techniques using more accessible materials like plexiglass. He eventually became Nigeria’s most recognized stained glass artist, with major commissions in churches across the country. Though a devout Muslim, he interpreted the commissioned themes with clarity and sensitivity, and always with his distinct visual style. Interestingly, there seems to be a symbiotic dialogue between the old paintings and the new glass works.

Grillo’s use of color and the emotional depth he conveys have inspired a new generation of artists, including Adeju Thomson, founder of the Lagos Space Programme. Thomson reflects: “I often think about how colour can create atmosphere. How it can communicate without being loud. Grillo’s work taught me that subtlety has power… Like Grillo, I am drawn to quietness and emotional depth. I am interested in aesthetics that do not over-explain. That make space for complexity.”

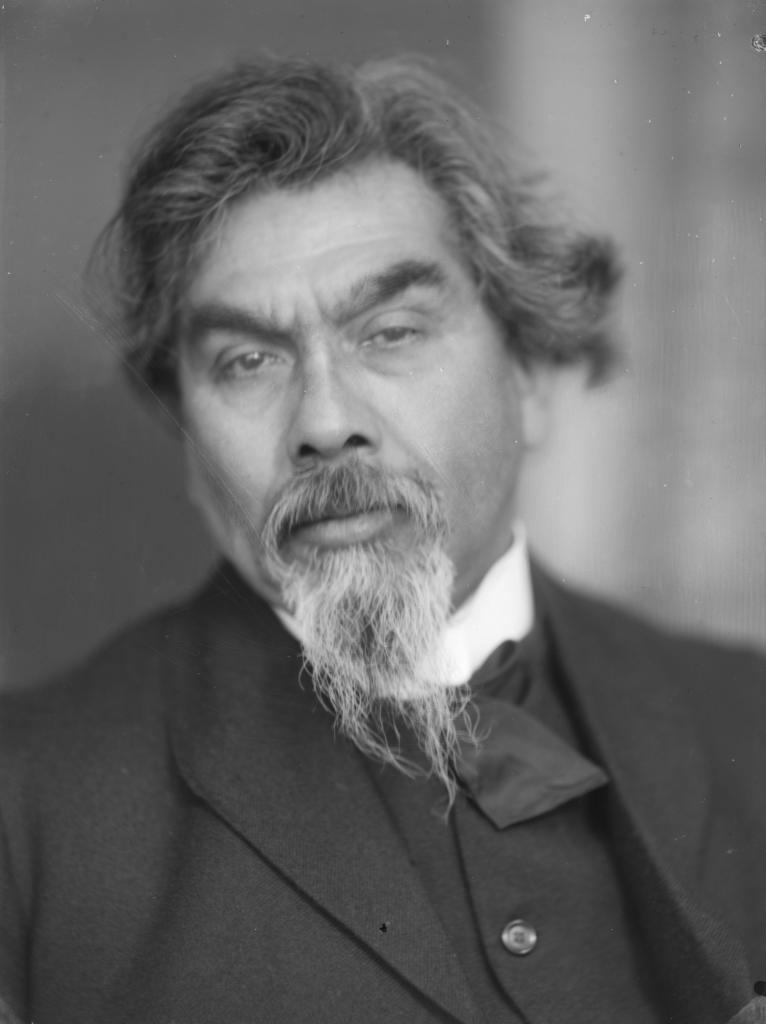

Like Grillo, Jan Toorop’s work is distinguished by a synthesis of indigenous cultural forms and Western techniques. Born in Purworejo, Java in 1858, the Dutch-Indonesian artist spent his early childhood in the Dutch East Indies before pursuing art in the Netherlands. Today, he is best known for his diversity of styles including Realism, Impressionism, Symbolism, Art Nouveau, Pointillism and Catholic Symbolism.

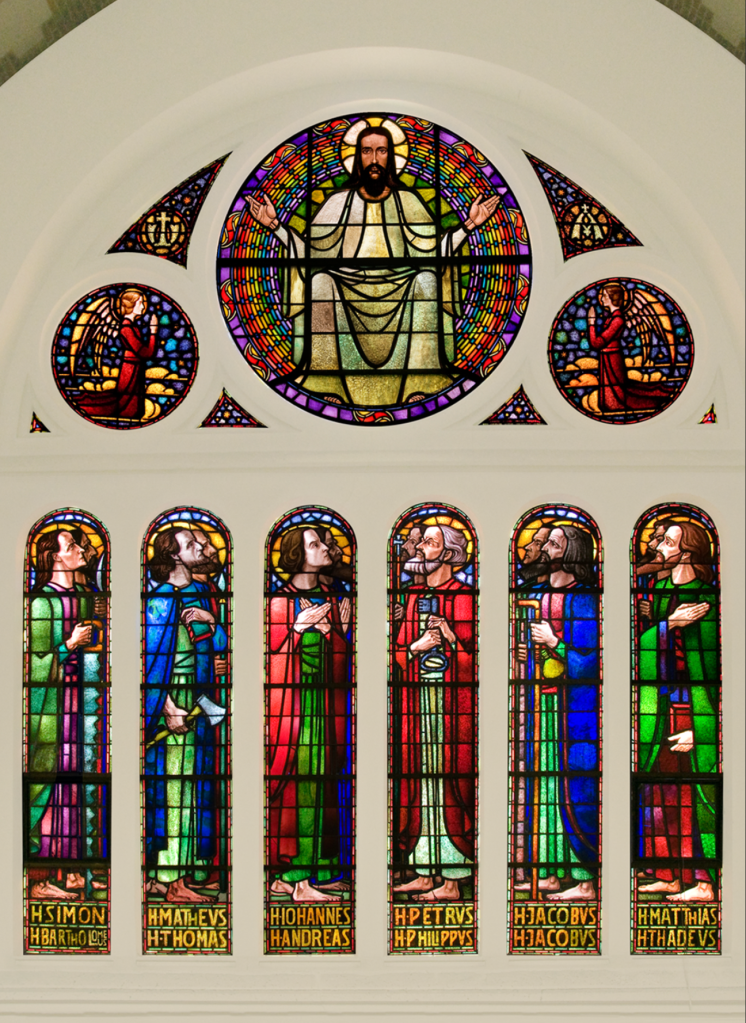

Toorop convened to this Catholicism in 1905, and various critics assert that from this date his work took on a placid tranquility, totally at variance with his pessimistic Symbolist stage. Toorop developed a strong interest in the integration of painting and architecture, which lasted the rest of his life. He went on to more tile work in the Aloysius Chapel of Haarlem Cathedral and began the large apostle windows in the Josef Church in Nijmegen. It is this latter project, completed between 1911 and 1915, that I draw upon to frame my comparison between Toorop’s stained glasses and that of Grillo.

Although the two artists have no direct connection, coming from different eras, artistic movements, and cultural backgrounds, they are united here in both subject matter and artistic process.

In fact, both artists received formal training in Western art institutions, yet each remained deeply committed to grounding their practices in cultural identity. Grillo studied Fine Art and Education at the Nigerian College of Arts, Science and Technology (NCAST) in Zaria. Alongside contemporaries such as Simon Okeke, Uche Okeke, Bruce Onobrakpeya, Demas Nwoko, and Jimoh Akolo, he developed the philosophy of Natural Synthesis, an ideology promoting the fusion of traditional African art with Western techniques to form a uniquely Nigerian modernism. Together, they later formed the Zaria Art Society, popularly known as the Zaria Rebels, a collective that would become instrumental in shaping postcolonial artistic discourse in Nigeria.

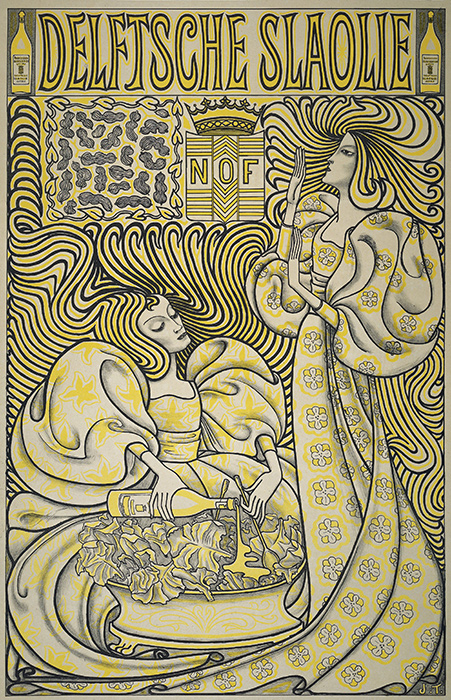

Toorop, meanwhile, trained at the Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten in Amsterdam, but his early years in Java continued to shape his artistic vision long after. This became especially evident during his Symbolist period, when he began incorporating Indonesian elements such as batik patterns, traditional clothing, and Javanese figures into his work.

Some recognized the artist’s Indonesian roots in Toorop’s depiction of Jesus. In 1931, in the book Java in Our Art, art historian and man of letters Gerard Brom wrote: “Toorop considers Christ primarily as the compassionate One, to whom, above the Nijmegen apostle window, he has given, if not Malay features, then, in conscious distinction from the blond Christ in so many Italians, dark hair and skin, in order to fraternally receive his beloved Java into the fullness of the firstborn Son of the Father.”

Critic Mieke Janssen observed of this style that “…. the severe mathematics and the clean lines make it seem to have the form of a building …. In the struct ure of this work, the lines give a suggestion of the Infinite.” These compositions are strongly oriented toward the vertical, with Christ invariably positioned as the central figure, flanked by groups that sometimes mirror one another. Yet, as Eileen Toutant has noted, beneath “the hieratic rigidity and stylized stances lies a force and emotional intensity that cannot be ignored.”

In the Apostles Window, Toorop has set the 12 symmetrical standing apostles in characteristic clear lines, two by two, each looking devoutly upwards to Christ, who is set in a round rainbow fringed window above. The apostles’ faces are realistic with one bearing the features of Cardinal Henry Edward Manning, a key figure in Toorop’s faith journey, and another that of the artist himself. The rainbow is the sign of God’s promise of faithfulness and the hands of Christ are stretched out in a sign of blessing. On each side are the Alpha and Omega but reversed, so that the end is the beginning.

A few years later, in 1919, Toorop painted Pandora. This figure adorned in traditional Indonesian attire, and enveloped in batik-like patterns, speaks to Toorop’s recurring theme of synthesizing his Javanese background with Western art forms, which recalls Grillo’s work. But the poised and angular position of the figure, reminiscent of the refined gestures in Indonesian dance and shadow puppetry, transcends a mere depiction of the “exotic”. It is, in effect, Toorop’s deliberate participation in the discourse on exoticism and the burgeoning spirit of Javanese cultural pride. Such representations symbolize Toorop engaged, and self-reflective discourse with prevalent themes of culture and self-awareness, employing art to navigate and articulate the layered facets of his multifaceted identity.

By comparison, as described by Chike Dike and P. Oyelola, Grillo “avoids photographic realism. Instead, he stylizes and elongates the figures in his paintings, which are easily recognizable by their slenderness, elegance, and grace; qualities he believes represent the contemporary ideal of beauty within an urban context.” An approach that clearly parallels Toorop’s stylistic language.

Although Grillo’s strokes tend to be more rounded, he uses in No Thanks a geometric composition that creates rhythm and order. Spanning almost meters in height, the glass comprises of stacked blocks of bright tonal fields, interspersed with diagonal strips of yellow, white, green and pink.

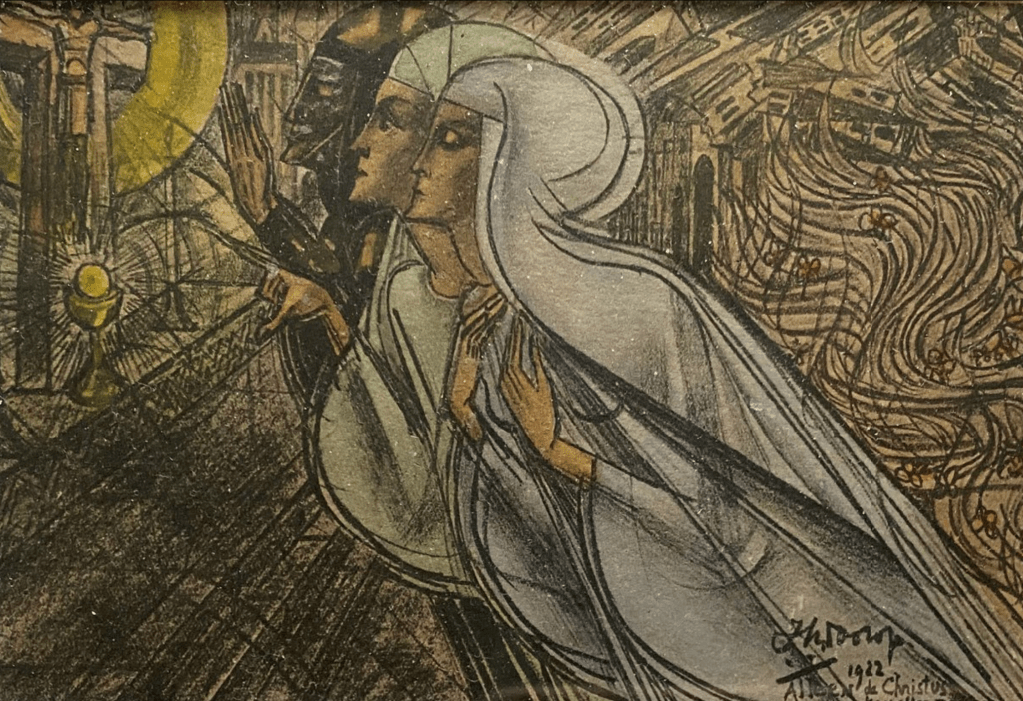

Other studies by Toorop, though more austere in tone, reveal a similar interplay of curves and flowing lines, what he once described as “the sounds that move through the world and uphold the faith.” For Toorop, these forms evoked “the pure and mystical periods of the past.”

WORKS CITED

Brom, Gerard. Java in Onze Kunst [Java Is Our Art]. W.L. & J. Brusse, 1931.

FURTHER READING

49thStreet. “The Zaria Art Society: Born of Artistic and Political Rebellion.” The49thStreet, 3 Sept. 2024, the49thstreet.com/the-zaria-art-society-born-of-artistic-and-political-rebellion/.

Grillo, Yusuf Adebayo Cameron, et al. Igi Araba : An Exhibition and Retrospective of Works by Yusuf Grillo, 2015, arthouse-ng.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Grillo_catalog-1.pdf.

Florida State University. “Athanor IV (Florida State University).” View of Vol. 6 (1987) | Athanor, 1987, journals.flvc.org/athanor/issue/view/5570/146.

“Jan Toorop Als Artistiek Vernieuwer En Devoot Katholiek.” Villa Mondriaan, 16 Sept. 2021, villamondriaan.nl/actueel/jan-toorop-als-artistiek-vernieuwer-en-devoot-katholiek/.