Thao Nguyen Phan works across painting, drawing, video, and installation, interlacing official histories with suppressed memories to consider Vietnam’s turbulent past and the social conventions, cultural memory, and rituals that shape the present. Trained as a painter in Vietnam, she turned to film while pursuing an MFA in Chicago and was recognized early on; from 2016 to 2018 she participated in the Rolex mentoring programme under Joan Jonas, a formative exchange that sharpened her attention to performance, the moving image, and narrative structure. Grounded in the literature, philosophy, and history of her homeland, Phan reflects on the social and ecological transformations wrought by colonization and extraction—using Vietnam as a lens through which to view rapid change across the Asia–Pacific.

The Sun Falls Silently is Phan’s first solo exhibition in France. Its title is drawn from Yasunari Kawabata’s Palm-of-the-Hand Stories (1916–64), whose brief, crystalline fictions capture essential turns of human destiny. In a comparable spirit, Phan brings her narratives to light with restraint and precision, re-reading historical accounts and collective memory through a body of works that read as a “ballad… for a wounded waterway.” She turns grief over historical injustice into paintings, light sculptures, projections, and films that imagine a better future, hoping “the audience can see the beauty and optimism amid these seemingly tragic stories.”

“History is written by the winners and when the North won the war in 1975, they rewrote history,” says Thao Nguyen in her deceptively gentle voice. “There was a lot of trauma.”

The exhibition unfolds as a conversation: guest artist Trương Công-Tùng (b. 1986) contributes two site-specific works as counterpoint, while facets of modernist sculptor Điềm Phùng Thị’s (1920–2002) practice extend the dialogue across generations. Together they form a polyphony of perspectives on country and history: its continuities, and ruptures.

Among the works, Ode to the Margins, a sculptural work of bamboo and thread, draws on ceremonial crafts of the Ba-Na people, one of the first Indigenous communities in Vietnam to adopt Catholicism. These ritual wreaths once used in ancestral ceremonies have been repurposed as Christmas decorations in the wooden Saint Mary’s Cathedral of Kon Tum, becoming emblems of faith, continuity, and adaptation.

No Jute Cloth for the Bones is an installation of jute stalks, a material typically consigned to firewood or to the makeshift architecture of low-income shelters. Stripped of fiber, the stalks appear like bare bones—without skin, flesh, or protection—while their faint percussive sound recalls a lullaby, a gesture of mourning for lives lost and separations left unresolved by war and famine. The work underscores the fragile membrane between past and present, life and death, and invokes Japan’s occupation of Indochina (1940–45), which contributed to a famine that claimed nearly two million lives as rice cultivation was displaced by jute. Then used for military and destructive purposes, this material becomes here a collective space of remembrance and reparation, like a curtain opening onto the rest of the exhibition. Jute fabric, traditionally used to block erosion in rice paddies, here prevents the erosion of memory.

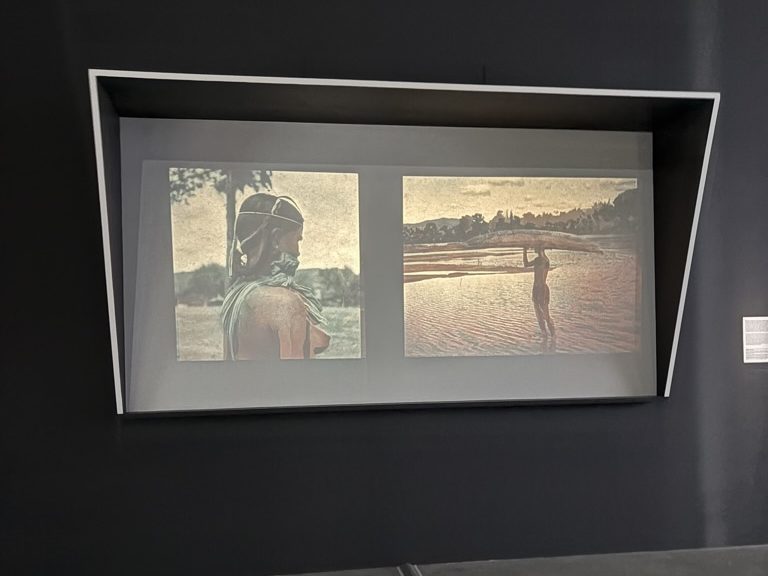

Several video works extend these meditations. Forêt, Femme, Folie (Forest, Woman, Madness) engages the archives of Jacques Dournes, the French missionary and ethnologist who lived among the Jarai of Vietnam’s Central Highlands. By reanimating his texts, drawings, and photographs, Phan challenges the authority of colonial anthropology and opens a space for alternative voices.

Palms of the Hand, an evolving experimental film, marks a new departure: setting aside strictly research-driven procedures, she embraces the expressive freedom of the moving image, creating sequences shot in historically charged landscapes that echo Kawabata’s fragmentary stories.

Intertextuality remains a constant across her practice. In the series Voyages de Rhodes, Phan takes a book by Alexandre de Rhodes, known for helping to romanize the Vietnamese language, as her canvas. By intervening with watercolor on his printed accounts (that at times recall the drawings of Francis Alÿs), she recasts colonial testimony as counter-narrative, restoring presence to voices long silenced.

Nearly 100 pages, on which she painted different scenes, are each individually framed and nailed perpendicular to the wall. Some are playful: children climbing water towers or bands of drummers marching in line. But elsewhere, Phan’s fantasy takes on a more sinister tone: as children appear harmed (disembodied); under duress (wearing blindfold), in a process of metamorphosis (the sexual organs of these children becoming tropical plants – such as papaya, sugarcane and dragonfruit) or undertaking an absurd task (such as attempting to use chopsticks without their hands as they kneel on the ground).

A page stamped White Optimism nods to poet Trần Dần’s (1926–1997) satire of socialist “black optimism.” Trần Dần, a major Vietnamese poet and a central figure in the Nhân Văn–Giai Phẩm movement of the 1950s, which called for greater artistic and intellectual freedom in North Vietnam. The work maps a Vietnam both familiar and estranged—wry, tender, and alert to how misreadings turn cultural difference into threat.