At the closing of the exhibition BODY OF MEMORY at Dagoma-Harty Gallery, artist M’Barek Bouhchichi and historian Pascal Blanchard engaged in a conversation on French colonialism and Black Moroccan portraiture, focusing on questions of visibility and memory.

Born in 1975 in the oasis town of Akka in south-eastern Morocco, Bouhchichi describes himself as carrying “a landscape that resists.”

“I know several Moroccos,” he explains. “One is the oasis where I was born, ninety-five percent Black. Moroccans often call me African, forgetting that they themselves are African.”

He adds, “In Arabic the Mediterranean is called the ‘white median sea’, a name that creates an island, a separation.” This feeling of displacement, captured by writer Leonora Miano in a phrase Blanchard often quotes, “When I arrive, I saturate the space” shapes both his life and his art.For Bouhchichi, painting Black figures forgotten by history is not a conventional artistic pursuit but a deliberate strategy of historical repair.

These men and women left their mark on France through remarkable and often pioneering lives, yet their stories have been systematically pushed to the margins of national memory.

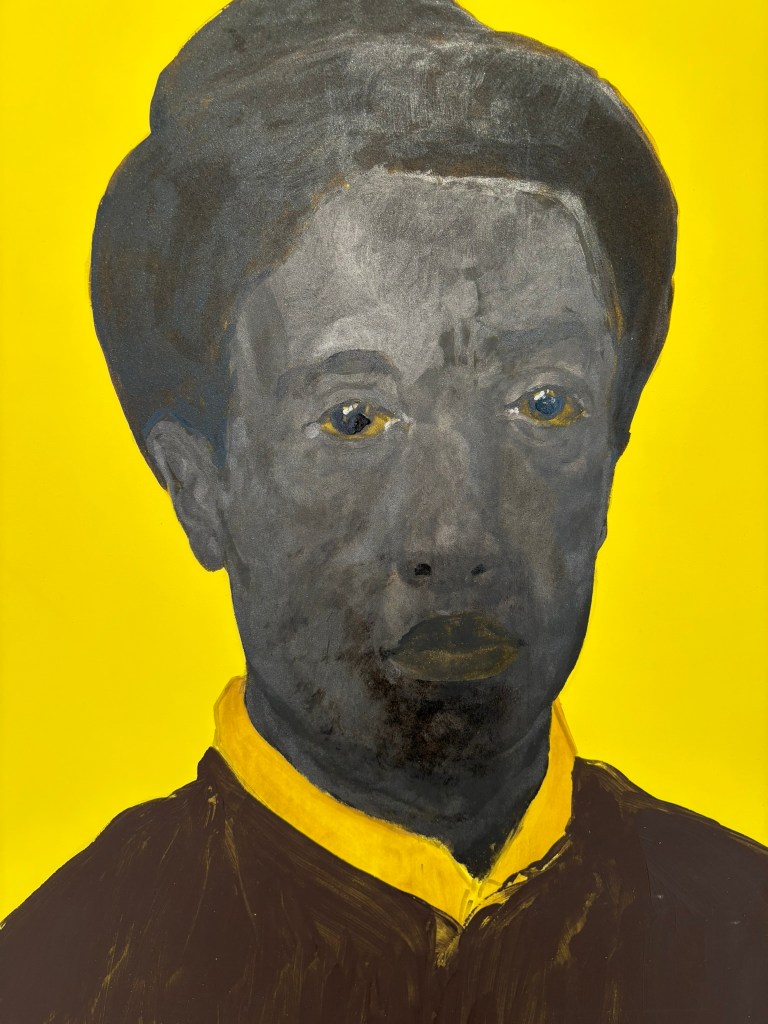

Through installations, paintings, and drawings, Bouhchichi develops a visual language that is both conceptual and tactile, a sustained meditation on the body and on otherness. His materials themselves carry the weight of colonial exploitation. Rubber, for example, recalls the violent extraction of the Belgian Congo while offering a palette of dense, saturated tones historically tied to representations of Black skin, colors that European eyes once coded as kitsch, raw, or excessive, echoing the bright patterns of wax fabrics and the fabricated “Africa” imagined by Europe. Brass, once cast into manillas that circulated as currency in the slave trade, and tar, a Renaissance pigment that grounds the surface like soil, serve as reminders of a past that refuses to disappear, a ground that still bears its scars.

Against these materials, his yellow backgrounds inevitably evoke Banania, the French colonial advertising icon whose smiling Senegalese soldier helped to naturalize paternalistic stereotypes. Bouchichi drains this yellow of its exotic charge and transforms it into an arena of confrontation, a place where caricature collides with a reasserted dignity.

One starting point in Bouhchichi’s work was the story of Severiano de Heredia — elected to the Paris municipal council for the Ternes district in the 17th arrondissement in 1873, who went on to become president of the municipal council of Parisin 1879 — and whose portrait has mysteriously disappeared from the city’s gallery of mayors. This loss sharpened his desire to create dialogues between figures who never met, to place Black bodies at the center of the gaze. “To look at them is to consider them,” he says, inviting even a silent, contemplative dialogue.

This ambition takes central stage in a brass triptych in which three panels carry quotations from two great travelers of the fourteenth century: Ibn Battuta, the Moroccan explorer from Tangier, and Wang Dayuan, his Chinese contemporary.

Their words are engraved in braille, reanimating a forgotten geography where Morocco marked the “Extreme West” and China the “Extreme East.”

Braille functions here as a metaphor for those who have been unseen, a democratic script that, as the artist notes, “reads everyone” without establishing borders.

Often treated as a foreigner the moment he opens his mouth, Bouhchichi embraces braille for its paradoxical combination of invisibility and universality.

Many of the figures that populate his work, he says, “imposed themselves on me like family.” Among them is Suzanne Roussi Césaire (1915–1966), the Martinican writer and co-founder of the journal Tropiques, whose incisive essays combined surrealism, poetry, and anti-colonial critique but were long overshadowed by the fame of her husband Aimé Césaire. The artist also highlights the Senegalese Tirailleurs, West African soldiers who fought in both World Wars but were long absent from French national narratives. During the colonial era, more people lived in France’s African colonies than in the metropolitan homeland, yet their political representation was minimal. History, Bouhchichi observes, was deliberately whitened to suggest that France was liberated by white soldiers alone.

In the 1980s and 1990s, descendants of the colonized began reclaiming these stories, asserting the need to say: “Don’t forget where I come from.” Yet France still lacks a dedicated museum of colonial history, leaving this past to float between popular culture and art. For Pascal Blanchard, images themselves become a form of evidence: even if images are contested today, they remain proof of what was once rendered invisible: territorial occupation, sexual violence, the exploitation of Black bodies.

M’Barek Bouhchichi reuses colonial advertising icons like Banania not to celebrate them but to prevent their quiet disappearance, arguing that if such images are no longer shown, the violence they encode will be forgotten.

How can this history be made visible?

Blanchard adds that naming streets after universally admired figures such as Martin Luther King or Nelson Mandela is not enough. The real challenge is not to honor people because they are Black, but to recognize those who made concrete contributions to French history and simply happen to be Black—and then to cultivate the curiosity to recover their names until they enter the everyday register of popular culture, until their presence becomes so ordinary that no one even stops to ask why a street bears the name of a Black mayor or a colonial soldier.

Is every act of remembrance inevitably political?

Both men agree that acts of remembrance are inherently political.

“Our minds are like mille-feuille,” Bouhchichi reflects, layer upon layer of inherited gazes and memories.

To remember together is to invite others into those layers and to insist that what was once silenced can, and must, still speak.