Coming back from an intense week at Frieze London, where I worked in the Focus section, I couldn’t help but compare how the two major fairs—Frieze London and Art Basel Paris—treat emerging galleries and artists. How do they each support, or fail to support, the artists and galleries trying to find their place in an already crowded art scene?

This year, Frieze London made a bold curatorial move by placing its emerging galleries right at the entrance of the tent, specifically to the far left as visitors walked in. Most people, upon entering, grabbed a floor plan and a copy of Frieze Magazine from the left-hand side and immediately found themselves immersed in the Focus section.

Comprising over 30 international galleries, Focus showcased artists from around the world: from El Apartamento (Havana and Madrid) to HARLESDEN HIGH STREET (London) and Petrine (Paris and Düsseldorf). To qualify for this section, galleries had to be under 12 years old, and booth prices (which ranged around £8,000) were relatively accessible for smaller players for whom fair participation is often a major financial stretch.

In contrast, the blue-chip giants, Gagosian, David Zwirner, White Cube, Hauser & Wirth, were placed in Section D, at the back of the fair. Yet even there, proximity to restaurants, cafés, and storage areas ensured a strategic advantage, both for visibility and comfort.

Across the Channel, Art Basel Paris (returning for its fourth edition this autumn) offered a very different model. The floor plan clearly favoured mega-galleries, the ones paying top rates and lending prestige to the fair. Upon entering, visitors were greeted by the towering booths of Gagosian, Pace, Hauser & Wirth, and David Zwirner.

Emerging galleries were literally and symbolically upstairs, tucked away in the Emergence section marked by a green banner. Those housed in the Galerie Seine enjoyed even less exposure, confined to small, dimly lit backrooms of the Grand Palais. Everything, from the carpet to the lighting, felt different, almost as if these galleries were part of a parallel fair.

I couldn’t help but imagine what it must feel like to work there for eight hours a day: technically part of one of the most prestigious art events in Paris, but in practice, excluded from its main stage: the iconic verrière. When someone says, “We did Basel Paris last year,” the image that comes to mind isn’t a cramped backroom but a gleaming white booth under that vast glass canopy.

This year’s edition included a range of practices, from photography at Document to conceptual installations at Lodovico Corsini. Yet it left me wondering: What is the real price of belonging to the Basel family?

Established artists already benefit from collectors, media coverage, and market visibility. But what about the thousands of emerging voices struggling for recognition? Does Basel Paris truly help bring their work to the international stage—or simply offer them an expensive illusion of belonging?

At Frieze London, there was a noticeably stronger sense of visitor engagement through performance and live programming. Although Frieze Projects no longer exists in London, this year’s edition brought back that spirit through several live works within the Focus section. At the Frieze Artist Award space, also located in Focus, award winner Sophia Al-Maria transformed part of the tent into a makeshift comedy club, performing a live set each day of the fair.

Stockholm-based Coulisse Gallery, for instance, presented Rafał Zajko’s Song to the Siren, featuring an endurance performance by Agnieszka Szczotka, seated motionless inside the sculpture for an hour.

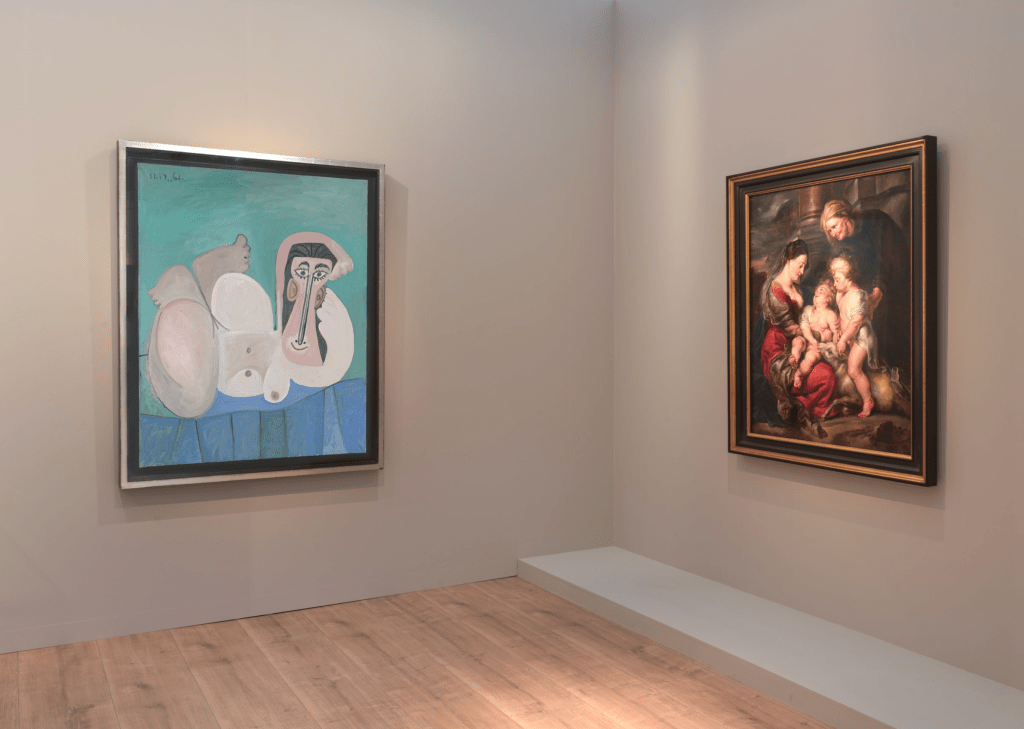

By contrast, my Basel experience was punctuated not by live moments but by masterpieces. The fair was dominated by early 20th-century works. Gagosian staged a dialogue between postwar and contemporary art with works by Rubens, Giacometti, Picasso, Currin, Fadojutimi, Rodin, Saville, and others. The Virgin and Christ Child with Saints Elizabeth and John the Baptist—Rubens’ painting that sold for $7.1 million at Sotheby’s in 2020—stood as a statement piece rather than a commercial one.

Pace also contributed to this aura with a 1918 Amedeo Modigliani painting, a Rothko, a major Picasso work on paper, and several Calder sculptures alongside pieces by Mary Corse, Lee Ufan, Agnes Martin, Robert Ryman, and Jiro Takamatsu.

It’s interesting to ask whether these mega-galleries like Pace or Gagosian are imposing their modern masterpieces on art fairs much like Trump imposed his tariffs on the world. For these mega players, fairs are surely less about selling and more about making a statement, provoking conversation, and media coverage.