Few names hold as much weight in the history of Japanese art as the Kanō family and the influential school that bore their name.

Founded in the fifteenth century by Kanō Masanobu (1434–1530), the Kanō School shaped Japan’s visual culture for nearly four centuries, sustaining unrivalled authority over official commissions and elite patronage while adapting its style to successive political regimes. Among its many generations of artists, Kanō Tan’yū (1602–1674) stands out as the defining painter of the early Edo period, representing the political and institutional structures that governed artistic production under the Tokugawa shogunate.

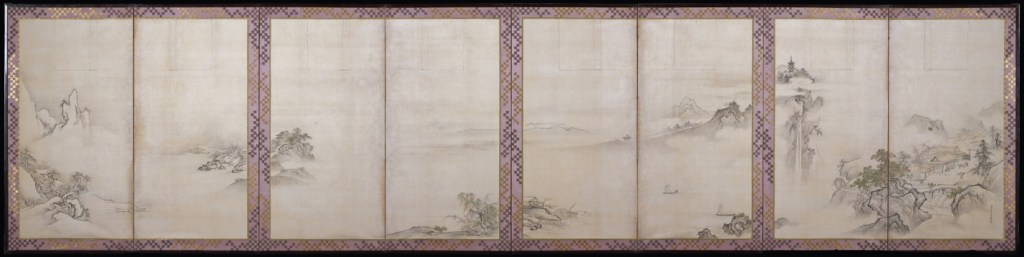

In fact, Tan’yū’s Eight Views of the Xiao and Xiang Rivers (1663) illustrates how artistic production operated mostly within a closely controlled system of elite patronage, in which painters participated directly in the mise-en-scène of Tokugawa power. Executed in ink and light color on paper, the pair of eight-panel folding screens exemplifies Tan’yū’s innovative aesthetic. He revolutionized the Kanō school by introducing a style more restrained than the grandeur popular during the preceding Momoyama era; one defined by a refined ink-monochrome palette and large areas of empty space that gave his paintings a subtle floating quality.

Eight Views of the Xiao and Xiang Rivers reflect the Edo-period fascination with kara-e (Chinese-style painting). Drawing on Song-dynasty poetry and painting, the theme depicts the misty river landscapes of Hunan province through eight canonical scenes such as “Evening Bell” or “Returning Sails.” Adopted by Tan’yū, the subject became a metaphor for the Tokugawa vision of harmony and moral order.

At fifteen, Tan’yū was appointed goyō eshi (official painter to the shogun), a role central to constructing the cultural legitimacy of Tokugawa rule. The political stability of the seventeenth century encouraged ambitious decorative programs for castles and the Kanō school was ideally placed to supply them—Tan’yū worked on such projects as the Nyogo palace (1619), Nijo castle (1624-1626), and Nagoya castle (1634), among others. In fact, from the fifteenth century onward, the shoguns maintained an official painting bureau (bakufu-edokoro), directed by the Kanō lineage, responsible for shogunal commissions, the restoration of earlier works, and the training of painters.

In this sense, the goyō eshi functioned as civil servants. As the “market” for such works was narrow, exclusive, and fundamentally political, this screen was not made for collectors or open sale, but to visually illustrate an ideological programme aligned with Tokugawa rule. Even informal activities like “table painting” (sekiga) required shogunal permission.

Within this system, painters were organized hierarchically. The oku-eshi (inner painters), including Tan’yū and his brothers Naonobu and Yasunobu, worked directly within the shogunal palace and received hereditary stipends, residences, and the right to wear the double sword of samurai rank. Below them were the omote-eshi (outer painters), who executed official commissions without the same privileges, and were the retained artists, employed exclusively by daimyō households. Moreover, materials, pigments, and themes were prescribed by rank and occasion.

There was also a hierarchy of subjects: landscapes (sansui) ranked highest, followed by Chinese figures (karabito) and bird-and-flower (kachō) paintings. Each genre corresponded to a degree of intellectual and moral value. Sansui, such as Tan’yū’s Eight Views, was the most elevated, representing cultivated detachment and moral clarity; it was therefore reserved for the highest patrons.

It should be noted that Tan’yū also produced works for private patrons beyond the shogunate: Buddhist priests, tea masters, wealthy merchants, and even imperial princes, although this part of his life is less documented. One of them was the priest Hirin Jōshō, who supported him for more than thirty years. Unlike many patron–artist relationships, Jōshō rarely dictated subject matter, leaving Tan’yū considerable freedom in what he produced. In exchange for works, Jōshō promoted him to important figures, brought him authentication requests, and payments often took the form of gifts or favours rather than formal monetary commissions.

The Kanō school’s ability to produce consistent work on a massive scale depended on standardization. Kanō Yasunobu (1613–1685), who led the main Edo branch, codified this system in his Private Guidelines for the Art of Painting (Gadō Yōketsu), where he argued that “achievement,” attained through rigorous study and transmissible through teaching, was superior to innate “talent.” Painters were trained to reproduce canonical models with precision, prioritizing collective continuity over individual expression. Copying from mohon (pattern books) ensured stylistic unity across Japan; even after losses such as the 1657 Meireki fire, archives were reconstructed from official collections.

All in all, political authority and institutional patronage largely framed Kanō Tan’yū’s practice, and, more broadly, the Kanō school’s production, by dictating subject matter, formats, and organisation. The school’s success lay in its ability to quickly grasp the tastes of the new rulers and adapt its output to meet political demands.

Yet the same system that secured its dominance also led to its rigidity. By the late Edo period, the school’s production had become repetitive, and new artists such as Kanō Sansetsu, Itō Jakuchū, and Katsushika Hokusai emerged to serve the tastes of an expanding urban merchant class. The transformation of the art market from an hereditary patronage to an urban clientele would eventually reshape Japanese painting altogether.