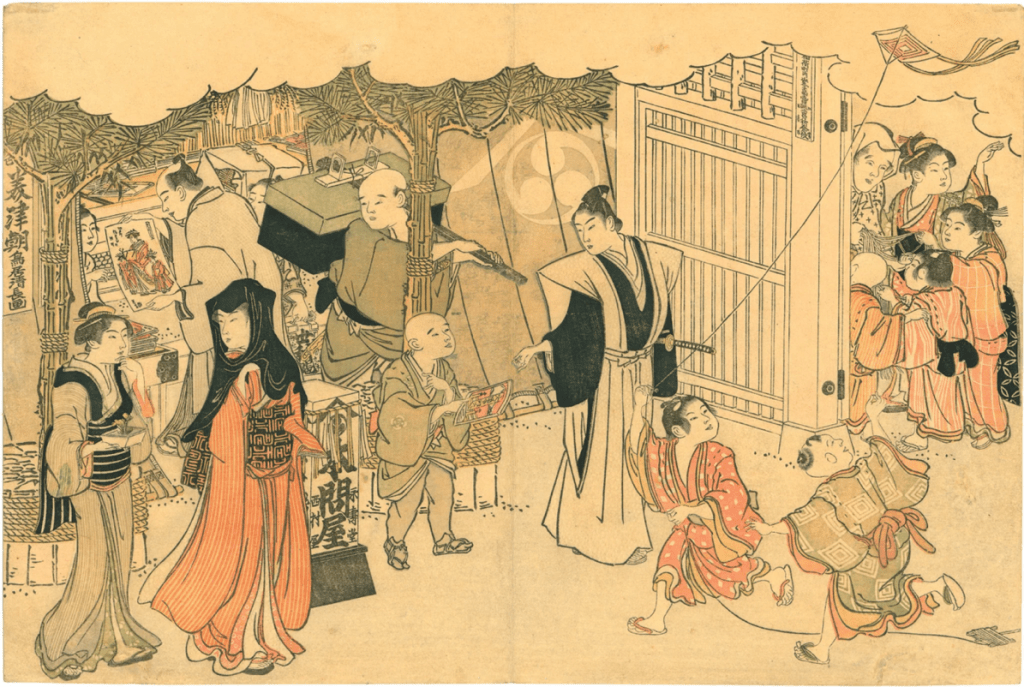

A Senjokō (仙女香) incense advertisement is visible on the right.

For decades, and in many cases still today, Western collectors and curators have focused almost exclusively on what they consider “authentic” Japanese art—works that appear traditionally Japanese in medium or style, such as nihonga, ceramics, lacquerware, or mokuhanga. A quick survey of Western “Japanese art” galleries or Asian art departments in auction houses shows how strongly this narrow lens persists.

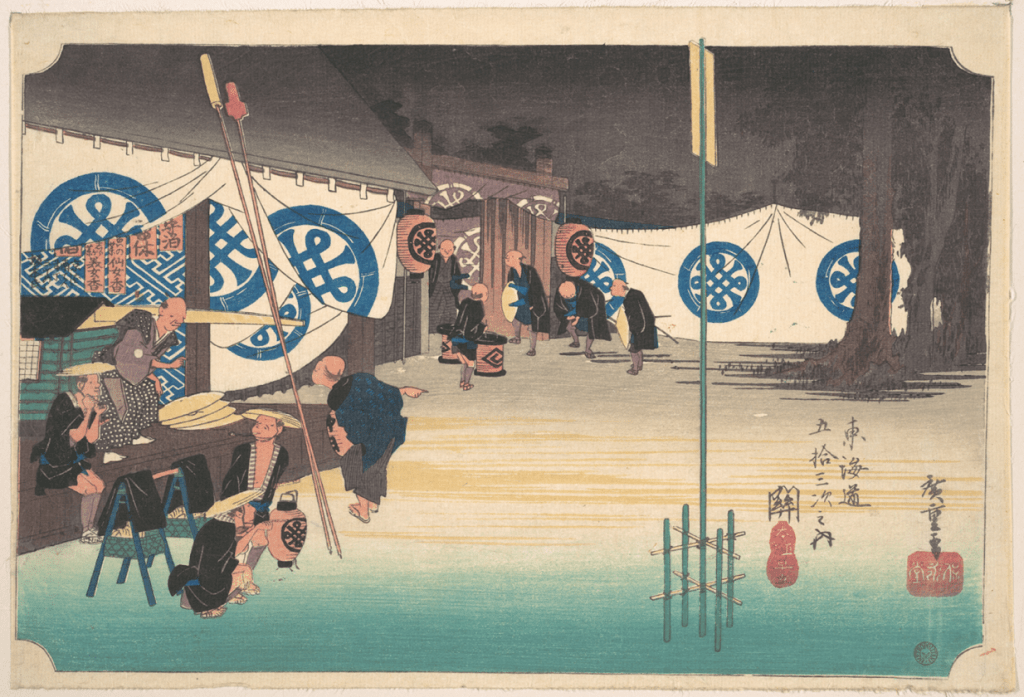

But catering Japan to this single prism is a way of reinforcing common orientalist fantasies, centered around the juxtaposition of the primitive and mystical East against the modern and industrialized West. It is therefore unsurprising that names such as Hokusai or Hiroshige, and images like the Great Wave, circulate widely, even among audiences without any interest in (Japanese) art. What is far less recognised, however, is that these artists could not have been so widely popularized without the Edo-period woodblock print publishers, who commissioned, produced, and sold their works. Woodblock prints inaugurated a new market model that aligned with the cultural practices of the ukiyo, the “floating world”. Initially shaped by Buddhist ideas of life’s transience, themes drawn from nature and folklore gradually gave way to images celebrating fleeting pleasure—an early form of joie de vivre.

The central question of this essay thus arises: Why can we consider Edo ukiyo-e publishers as Japan’s first art dealers? As straightforward as the question may be, it has never been asked. The role of the art dealer has rarely been examined in the Japanese context, partly because the figure of the “art dealer” is rooted in a Eurocentric history of the market. Yet Edo publishers occupied a position that invites comparison, and this essay will highlight a number of remarkable similarities and differences between the two markets. I will offer analysis on how, in many aspects, publishers acted as proto-dealers, operating as economic engines and cultural intermediaries.